5 min.

About six years ago, my oldest emailed one of her short whimsical videos. She’d teasingly set up the camera along a 5 foot tall white picket fence at the end of the sidewalk, and it captured her, just visible above and below the fence bobbing along the path on its other, hidden side. Her message playfully hinted that something was coming. I couldn’t guess what it could be, but I felt a kind of dread.

Her story is somehow nested in mine, some scenes could have been spliced together, one continuous reel. Of course, the setting and characters changed, yet my oldest and I are said to be alike. Maybe. Our histories are, after all, not entirely our own but shaped by our coming of age at a certain moment.

Bookend events span both my girlhood and that of my girls. We grew up under the shadow of assassinations. Just at the turn of the century, my daughters likewise experienced grief and trauma as the general confidence of an earlier era met with plane-crashed towers. Americans collectively lived traumatized, first by JFK’s murder, then the fall of the Twin Towers.

Permanently imprinted on our collective memory, the Fallen Man photo captures a Twin Towers victim plummeting to his death.

As a girl, I relied on the palpable goodness of my parents, Walt and Glenna Sanders, who’d grown up during the Depression, coming of age and marrying with the Second World War. They couldn’t guess the chaos of the Sixties would unsettle family life so fiercely upheld by their generation. Reflecting the unflagging optimism of the age, my mother’s faith in God was matched only by her confidence in American enterprise to raise secure self reliant kids and to overcome social ills.

My father completed his doctoral work supported by my mother’s night shift nursing job. I was born fifth of six kids in Champaign, Illinois, and soon we moved to Maplewood Drive, living on a cul de sac with strawberries running along the side length of the house and a bountiful peach tree and raspberries in our back yard. The matching hedge rows of bordering neighbors grew a lush green arch forming a shaded tunnel. Many of our running games involved racing full tilt down that green tunnel.

Our milk came in crystal clear glass bottles, nested in a tin lined box on the front porch, and replenished weekly. My brothers Paul and Eric delivered enough newspapers to afford them the newest bike. Eric, my favorite brother, bought a sting-ray type with an elongated seat, very cool. Once, he brought home an injured bird he’d spotted along his route, and we nursed it back between all-day ping pong battles in our garage. My mother, with her strong square jaw and jet black hair, once pulled back severely under her nursing cap, now framed her face in a regular permanent. At lunch time, I walked home to 2503 Maplewood, and I still recall the warmth of the thick green pea soup my mom set out to welcome me.

This photo shows the house next door to 2503 Maplewood.

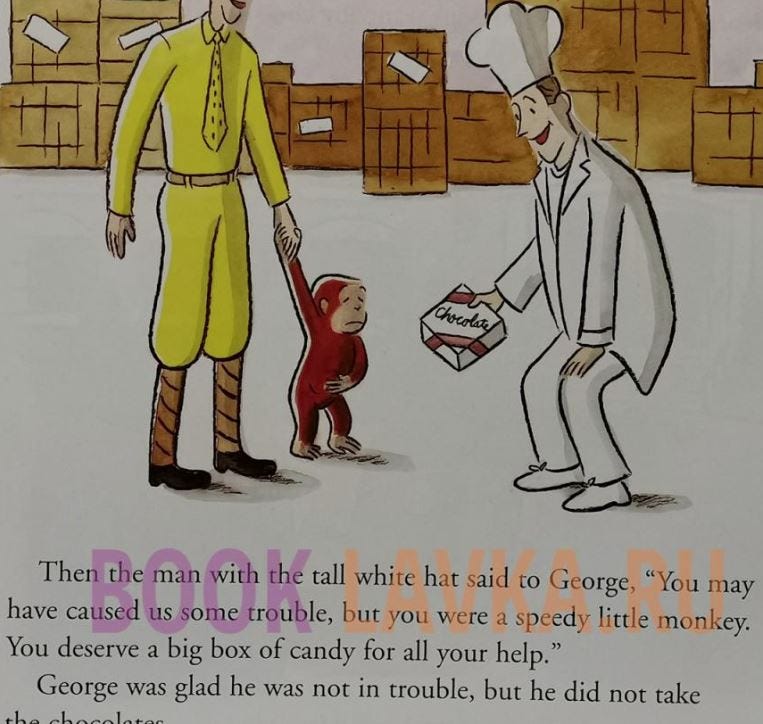

My mother’s vision of the world felt right, one in which literacy could overcome any difficulty. About that time, the book-mobile arrived. Stepping onto the bus bookmobile and perusing the library of picture books, I swept up every one of the Curious George books which like the movie portrayals of the 50s captured the overweening positivity of the era. Whatever mischief George caused was resolved by his towering friend, and every time, bad consequences were swept aside by that man with the yellow hat. What kid—or politician-- wouldn’t like a man with a yellow hat?

It’s as if the popular film Forrest Gump picks up motifs from the favorite kid’s book Curious George, where the disaster caused by the episodic chaos caused by letting the monkey go free is resolved with an extrinsic reward of a box of chocolates. In the film, Forrest’s mom offers a similar inanity. “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.”

The much-loved book earned a cameo in the boomer parody Forrest Gump, which my sister-in-law sent us in 1994. In it, Forrest races forward as readily on the football field as the field of battle. American resilience is mocked as Forrest combines a simpleton’s faith in such values as American ingenuity and a nonstop spirit of enterprise. Forrest is met with simplistic non-answers first from his mom, then from his society. The Sixties were full of kiddie- level platitudes such as “Try it, you’ll like it.” With Candide- like optimism, Gump yields to the self- destructive Jenny’s seductions, becoming boyfriend and spouse to a woman who uses him in her drive for sex, drugs, and activism.

Not unlike the flag-waving zeal of the era, the film critiques a culture designed to curb curiosity. As with the conspiracy theory labeling of inquisitiveness about what might be driving America’s geopolitics, the CIA-backed assassinations of the period are flashed in MTV fashion, the Gumpification of an American public determined to embrace values like patriotism even in the midst of bald-faced betrayal by political leaders.

In 1994, I was an NPR listening liberal urban mom teaching composition to undergraduates at Ferris State University in Michigan. I read to my kids about the mischievous monkey whose mishaps, like the government’s, could be swept up by the man in the yellow hat.

And later, much later, after we’d moved our family to Indiana, I’d jumped up from my chair — the Zoom therapist beginning to interpret my young adult child — saying “It’s political!” This grotesque moment fell out of its cartoon frame. In the Zoom set up, my oldest and her therapist set out to re-educate us. They spoke out of the screen as out of a darkened cinematic panopticon.

Stepping into the limelight was incredibly this tall adult, a licensed therapist, Mary Collins to be precise, Alabama’s gold-haired go-to counselor for on-demand gender. I see her even now, leaning in as if to take our hand and lead us out of this trouble.

She is the man in the yellow hat.

- - -

The world's greatest wisdom can always be found in picture books.